Stick and Rudder: What you learn from getting a tailwheel endorsement

I want to share my experience in getting a tailwheel endorsement, what I learned about flying, and about the general aviation community. If you’ve been thinking about getting your tailwheel endorsement, hopefully my story can help separate the facts from myths, and help you know what to expect along the way.

Not long after I started my Private Pilot training, I started seeing tailored posts on my Instagram feed of lavishly equipped Carbon Cubs performing stunts out in exotic and beautiful locations. Sometimes, the pilot would be skimming their 31″ Alaskan Bushwheel tires just on the river’s surface at sunset, creating a perfectly controlled spray trail (warning: do not do this), either to then land on a tiny sandbar or merely to show off. In other clips, the pilot would perform a butt-puckering slip over frosted tree tops, then land on a beach below, turn around and back taxi all while never letting the tailwheel touch the ground. Or there’s this clip of someone in an experimental SuperCub seeming to hover in mid-air before landing like a dainty butterfly with no ground roll on the Knik River in Alaska.

I’ll admit, the showmanship was very inspiring to me, and offered a (potentially misleading) glimpse into the world of tailwheel flying. I wondered how these pilots learned to do things like that, and what kind of lives they had. I started following the #STOL (Short Takeoff and Landing) hashtag on Instagram and started falling in love with certain classic airplane models as my exposure grew. A tailwheel endorsement quickly climbed to the top of my aviation bucket list, even as I moved right into instrument training at school.

Lewis University, a Part 141 school, didn’t offer a tailwheel endorsement, probably because most students wouldn’t need one on their way to the airlines. Yet as far as I could tell, the skillset is currently in high demand for its likelihood to improve a pilot’s landing skills (and more), and for its ability to unlock access to another kind of aircraft with “conventional” landing gear, another religion for some. Thus, I was on my own as far as finding a qualified CFI operating around Chicago and coming up with the funds (No, it’s not covered under the GI Bill.) and spare time between work and school.

Finding a CFI

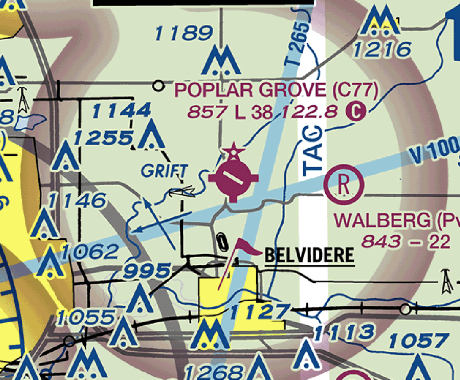

My search led me to some popular destinations in the Chicagoland area with which I had become familiar as a student pilot. Not really knowing what to look for, I simply inquired about the plane and price.  Expect to pay around $1500 for 10 hours of instructor and wet plane. You can learn in a 1946 Aeronca Champion 7AC “Champ” with A&M Aviation at Bolingbrook’s Clow International Airport (1C5), a place where many a Midwest pilot has had their $100 hamburger for years at Charlie’s Restaurant. Poplar Grove Airmotive at Poplar Grove airport (C77) outside Rockford offers training in both a 1946 Piper J3C-65 Cub and a 1948 Cessna 140 as a single tailwheel endorsement package, which was great because I had drooled over both of these models at length on Barnstormers. I also happened to be virtually acquainted with the CFI offering tailwheel instruction at Poplar Grove, Lana. So after one phone call, I was on the schedule.

Expect to pay around $1500 for 10 hours of instructor and wet plane. You can learn in a 1946 Aeronca Champion 7AC “Champ” with A&M Aviation at Bolingbrook’s Clow International Airport (1C5), a place where many a Midwest pilot has had their $100 hamburger for years at Charlie’s Restaurant. Poplar Grove Airmotive at Poplar Grove airport (C77) outside Rockford offers training in both a 1946 Piper J3C-65 Cub and a 1948 Cessna 140 as a single tailwheel endorsement package, which was great because I had drooled over both of these models at length on Barnstormers. I also happened to be virtually acquainted with the CFI offering tailwheel instruction at Poplar Grove, Lana. So after one phone call, I was on the schedule.

Lana is decidedly living the real-life general aviation dream. As a young CFI with her own 1947 Piper PA-12 Super Cruiser (“Super Bruiser” as she calls it), she wears two hats at Poplar Grove as flight instructor (primarily tailwheel) and full-time A&P apprentice. When you picture that old retired crow offering float plane trips around the Florida keys, having spent years as a totally self-sufficient pilot in the remote Alaskan bush — Lana is who they looked like when they were really young and healthy … or perhaps I’m just projecting my own aviation fantasies on someone who is really walking the walk.

In any case, I was happy to have her as my instructor as she embodied precisely the same enthusiasm, admiration and general geekiness that led me to embark on this tailwheel endorsement journey in the first place. I won’t forget our first meeting as she came up from the engine shop wiping her hands on her oil-stained jeans, grabbed a handheld intercom and led me to a dirt hangar where I saw the Cub for the first time.

Lesson #1: V-speeds? No, no V-speeds.

There’s a reason the J-3 Cub continues to be one of the most iconic light aircraft of all time, as well as one of the most sought-after tailwheel trainers. Its minimal aesthetic and nimble handling invites pilots at any experience level to part ways with bad habits, and requires them to engage all their senses throughout the phases of flight. The lack of instruments and physical space can be claustrophobia inducing to the uninitiated, e.g. pilots used to scanning a typical six pack.

I found myself running through ATOMATOFLAMES as I peered inside the small cabin for the first time. It checked all the boxes, sure. I remember Lana saying, “no electrical whatsoever,” casually as she listed off other specs.

Wait, no electrical system? That means … no radios? No ADS-B? No starter?

Nope. In fact you need to check the windsock as you taxi, since the nearest reliable AWOS is at Southern Wisconsin Regional (KJVL). You need to make your visual scan for traffic reliable, especially in the pattern, especially when multiple runways are in use. The roads replace a heading indicator. You can try to use the Cub’s magnetic compass, but the vibration of the elderly Continental A65 engine mounted with no dampening contributes greatly to oscillation error. After a few moments in the air, you realize there is almost no point in scanning the instruments, and there’s a reason every seat in the Cub is a window seat — it’s best to keep your eyes outside.

The aircraft has been meticulously whittled down to only that which is essential for flight — the same equipment that was essential in the 1940s: the pilot, the engine, the prop and the wing. Having removed many distractors, now the pilot can learn very quickly. The whooshing sounds of air hitting the struts and cowling can cue you in to minute changes in airspeed, which should be no surprise if your sight picture with the horizon has changed. The “mushiness” of the stick can be an early stall warning. If you feel more weight on one side of your ass at any time, you’re likely uncoordinated, a predictable result of the Cub’s conspicuous adverse yaw observed while rolling into a turn, easily corrected with opposite rudder.

With some practice, you can sense the quality of your approach in terms of airspeed and altitude without any help from the instruments, but it’s a good idea to cross check. You can sense when small power adjustments or a slip is necessary. You can even sense when you are just a few inches from the earth, hold it there long enough to bleed off any excess airspeed and stall at the precise moment you are in a 3-point attitude and touching the ground — and the first time that happens on purpose is a proud moment. But if it wasn’t on purpose, it’s important you still take credit for it.

Here is the part where I think Instagram could be somewhat misleading. It’s easy to look upon the CubCrafters XCub with lust, with its 1500-plus FPM climb rate and glass panel. But had I started my tailwheel journey with anything more than 65 horses, I feel like I would have missed out greatly. I didn’t find myself missing any instruments in particular either. Maybe that’s a little elitist, and I suppose people who have $297,000 to spend can spend it however they like, even on a Cub capable of flying itself.

What’s in a tailwheel endorsement?

Most tailwheel endorsement courses follow the same curriculum, which should be no surprise. Though 14 CFR § 61.31 (i) only requires that a short set of maneuvers be included in the endorsement:

- Normal and crosswind takeoffs and landings;

- Wheel landings (unless the manufacturer has recommended against such landings); and

- Go-around procedures

I’m not sure of the reason, but the FAR doesn’t mention a normal 3-point landing specifically, which seems like a fundamental skill. It could depend on the CFI, but there are a few other maneuvers I was happy Lana included in my short course:

- Steep spirals

- Side slips, forward slips

- Power-off 180s

- Short-field takeoffs and landings, soft-field takeoffs and landings

- S-turns while taxiing

Mostly, we did a lot of pattern work. I racked up more than 50 landings within a few days. I noticed my patterns getting tighter and lower. We practiced on the grass runway at Poplar Grove for the majority of the training, and switched to the paved runway and the Cessna 140 as my skills improved. We practiced briefly at Dacy Airport (0C0) where the grass strip is so bumpy, it really teaches you the value of getting the mains off the ground early and remaining in ground effect. Also I think Lana wanted to catch a glimpse of a Stearman she happened to know was there.

Flying Low and Slow

The few moments between takeoff and short final or heading back from the practice area were spent aircraft spotting with Lana, and became easily half the value of my endorsement without exaggeration. I was particularly excited to spot an exceedingly rare Beech 18 (N8389H) owned by Poplar Grove Airmotive. We saw several gorgeous Waco biplanes, the owners of which seemed to be content merely taxiing around for hours. I spotted and later chased down the owner of a Luscombe 8A to get a few pictures.

Lana was able to talk at length about nearly every aircraft we encountered and its owner, and the unique characteristics of flying or maintaining each aircraft. She even knew what those owners did for a living, and could predict whether they intended to stay in the pattern or depart even though we weren’t using a radio. As I would later learn, this is about normal when you make a CFI watch their favorite movie (The Pattern) over and over again for hours each day at 500-1000 ft. AGL. That is to say, Lana has flown many a traffic pattern, her arms unfolding only to brace for her students’ inevitable bounce down the runway, her eyes scanning the skies, the ground and everything in between.

It’s a slow, ritual torture endured by many CFIs who need the hours and experience in order to meet baseline airline qualifications. But as the industry continues to be ravaged by COVID-19, many up-and-coming pilots may not have that dream job waiting for them once they’ve done their time in the right seat with students, er … front seat in Lana’s case. As a young CFI interested in general aviation, Lana was able to carve a niche for herself as a tailwheel instructor. It helped her land a job during the height of Illinois’ COVID mitigation efforts, which should tell you how valuable the skillset has become for flight schools — not despite COVID but perhaps because of COVID.

Pilots who were focused on their hours before are now wary of the long-term effects the virus will have on hiring, and are realizing it could be a while before the job market recovers. They’re choosing now to bide their time and focus on skill building. And for many that means hopping in a taildragger for the first time. The same goes for more experienced pilots who never found the time to earn the coveted endorsement.

Conclusion: Managing Expectations

It could be a win-win for pilots and flight schools, minus the part where people seem to have some strange fantasy of being taught tailwheel only by old geezers. I wish I was kidding. It’s just another systemic issue Lana has learned to forgive as she encounters students who blatantly question her abilities and experience while they biff wheel landing after wheel landing. If you ever happen to watch a bruisy blue-haired 85-or-older man do a hand prop, it will literally terrify you. Be glad if your tailwheel instructor, or any CFI for that matter, is someone who you can actually talk to.

Also, remember that along with gaining new skills, we can potentially gain new friends, which is part of why I liked venturing out and seeing the Chicago aviation community. It’s just exposure you don’t get at a Part 141 school, and it really helped me see the bigger picture.

I loved this story! I am normally not ever one to leave a comment on a story, but after doing some digging on why I should get my endorsement I found that I could relate to this story and enjoyed reading it. Keep up with the good work of writing and flying!

I am so glad you enjoyed it! I will keep writing and flying!